Thomas Harold Massie, Bio, Age, Education,Career, Net Worth

Thomas Massie, Biography,

Thomas Harold Massie was born in the deep winter of 1971, a son of Kentucky soil who would grow into both engineer and lawmaker, a man equally at ease with circuitry and the Constitution. He carries the quiet precision of someone trained to measure twice and cut once. Numbers first shaped his mind. Then politics claimed his voice.

Thomas Massie Lewis County Judge

Before the marble halls and late-night votes, there was a county courthouse in Lewis County, where he served as judge-executive for a brief but formative season. It was local government in its rawest form, roads, budgets, neighbors. Responsibility felt immediate there. Personal.

Long before that, he walked the corridors of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where ideas hum and ambition sharpens itself against steel and silicon. He founded a startup in Massachusetts, translating theory into enterprise, invention into livelihood. He built things. Then he turned toward rebuilding what he believed politics had neglected.

In 2012, he stepped onto the national stage as the representative for Kentucky’s 4th congressional district, a region stretching across northeastern Kentucky, anchored by the Cincinnati skyline on one edge and Louisville’s eastern suburbs on the other. It is a district of river towns and commuter highways, old farms and new subdivisions. He speaks for all of it.

He has often been called a libertarian Republican. A Tea Party insurgent. Labels follow him, but he seems more at home in dissent than in comfort. His politics lean toward restraint, of government, of spending, of power itself. He questions loudly. Sometimes alone.

During Donald Trump’s second administration, Massie became a persistent critic, challenging the president over the release of the Epstein files, over sweeping legislation branded the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, over the use of American force abroad. The disagreements were sharp. Public. Unmistakable.

And politics, being what it is, answered in kind. Trump moved to encourage a primary challenge against him in 2026, signaling that independence carries its own cost.

Massie remains, as ever, an engineer at heart, probing systems for flaws, skeptical of excess, inclined to test every structure for stress. In Washington, that makes him a friction point. In Kentucky, it makes him familiar.

Thomas Massie Birthplace

Thomas Massie was born in Huntington, West Virginia, where the Ohio River moves with quiet authority and the hills hold their stories close. Not long after, his life took root across the water in Vanceburg, Kentucky. That is where he was raised. That is where the land began to shape him.

Appalachian culture wrapped around his childhood like a well-worn coat. Plainspoken, self-reliant, wary of distant power and proud of local grit. The rhythms were steady. Church bells, school days, river fog in the early morning.

His father worked as a beer distributor, navigating back roads and small-town storefronts, building a living mile by mile. It was honest work. Practical work. The kind that leaves little room for pretense.

At Lewis County High School in Vanceburg, amid lockers and Friday night lights, he met Rhonda. First love arrived without ceremony. It simply grew, as naturally as the hills that surrounded them.

The town was small, but the world ahead was not. And yet, even as horizons widened, the contours of that Appalachian beginning, its resilience, its independence, its quiet stubbornness, remained etched into him, steady as the river and just as enduring.

Thomas Massie Education

Thomas Massie arrived at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the quiet intensity of someone who had already imagined himself there. As a boy in seventh grade, he had watched the school’s famed design competition on television and made a private vow. One day, he would not just attend MIT. He would win.

He earned his Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering in 1993. Three years later, he completed a Master of Science in mechanical engineering. Circuits and gears, code and force, he moved easily between them, drawn to the hidden logic inside machines.

His master’s thesis carried a title both technical and visionary: “Initial haptic explorations with the phantom: virtual touch through point interaction.” It explored the frontier where human sensation meets digital reality, where touch itself could be simulated and transmitted through a machine. The work was precise. The implications, expansive.

But Massie was never confined to the laboratory. In 1990, he joined the MIT Solar Electric Vehicle Team, helping to build a car named Galaxy, a sleek embodiment of sun-powered ambition. Metal and sunlight. Calculation and courage.

When the team entered the 1990 GM Sunrayce, it was Massie who took the wheel. For ten days, the race stretched across miles of highway and heartland, ending at Churchill Downs beneath the wide Kentucky sky. They finished sixth. It was not victory, but it was triumph enough, a testament to endurance, design, and belief.

Then came 1992. The 2.70 Design Competition, “Introduction to Design and Manufacturing,” now known as 2.007, stood as one of MIT’s most storied proving grounds. Professor Woodie Flowers, who had pioneered the contest, would later recall that Massie had dreamed of this moment years earlier. And when the day arrived, he did exactly what the younger version of himself had promised.

He won.

It was the kind of victory that closes a circle. A boy watching a television screen in awe becomes the young engineer standing at the center of the arena, proof that ambition, once planted, can hum quietly for years before it sparks into light.

Career

In 1993, fresh with ideas and restless ambition, Thomas Massie and his wife founded a company they called SensAble Devices Inc. It was built on a simple but radical promise: that a person could reach into a screen and feel what was not physically there. Digital objects would no longer be distant images. They would press back.

That same year, he completed his Bachelor of Science at MIT, his thesis echoing the work that consumed him: “Design of a three-degree of freedom force-reflecting haptic interface.” It was the language of engineering, exact and deliberate. Behind it lived a larger dream, the merging of touch and technology, human sensation carried across circuits.

Recognition came quickly. In 1995, he won the Lemelson-MIT Student Prize for inventors, along with its $30,000 award. Soon after, he claimed the $10,000 David and Lindsay Morgenthaler Grand Prize in the sixth annual MIT $10K Entrepreneurial Business Plan Competition. The ideas were no longer confined to prototypes. They were becoming enterprise.

By 1996, the company had evolved. Reincorporated as SensAble Technologies, Inc., it gained new partnership when MIT’s Bill Aulet joined the venture. The vision widened. Capital followed.

Over time, Massie raised $32 million in venture funding. The company grew to employ seventy people. Patents accumulated, twenty-four in all, each one a small fortress protecting innovation. Laboratories buzzed. Investors watched. The invisible world of virtual touch became tangible business.

In 2003, he sold the company. A chapter closed. Yet the pattern was already set: identify a system, study its hidden mechanics, and reshape it with conviction. Whether in technology or in public life, he seemed drawn to the same challenge, making unseen forces felt.

Thomas Massie Wife

In 1993, Thomas Massie married his high school sweetheart, Rhonda Howard, the girl he had met in the familiar halls of Lewis County High. They were young. Certain. Together, they stepped into a wider world.

They attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology side by side, bound not only by marriage but by shared curiosity. While he pursued his path through electrical and mechanical engineering, she earned her own degree in mechanical engineering. Their partnership was intellectual as well as personal, problem-solving at a kitchen table, ambition folded into ordinary days.

They built a life that stretched far beyond campus. Four children followed, each one a new center of gravity. Home became a place of motion and noise, of school mornings and late-night conversations, of seasons marked by growth.

On June 27, 2024, Rhonda died at the age of 51 in Scioto County, Ohio. The loss was sudden and deeply felt. An autopsy later determined that she died of respiratory complications of chronic autoimmune myopathy, with multiple additional autoimmune diseases contributing to her death. Massie confirmed the findings publicly, giving language to a grief that could not be contained by it.

The years they shared remained. The family they raised endured.

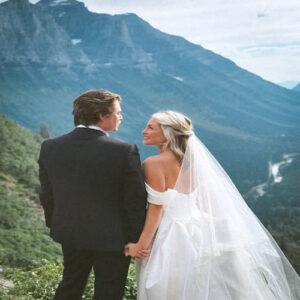

On October 19, 2025, Massie married Carolyn Moffa, a former congressional staffer for Senator Rand Paul. Life, in its quiet insistence, moved forward. Love returned in a different form, no less steady, no less real, carrying with it memory, resilience, and the long echo of everything that came before.

Height and Weight

In the halls of Congress and out on the farm, Thomas Massie carries himself with a presence that is both grounded and unpretentious, like someone shaped by Appalachian skies and long Kentucky roads. He is often described as standing around six feet tall (about 1.83 m), a height that neither seeks attention nor shrinks from it, but simply fits the frame of the man who strides between machine shops and legislative chambers.

His build is less often captured in official stat lines than his determined gaze, yet available profiles paint a picture of an average, healthy weight for a man of his height, reflecting an active life spent outdoors and on his feet rather than in pursuit of any athletic record.

There is something fitting in these measures: neither towering nor slight, neither overly robust nor fragile. Massie’s physical presence mirrors his persona, practical, steady, and quietly confident as he moves through fields of corn or corridors of power, guided by the same deliberate logic that once built virtual touch into reality.

Thomas Massie Net Worth

Wealth, for Thomas Massie, did not arrive as inheritance or accident. It was engineered.

Between 2016 and 2018, financial disclosures analyzed by OpenSecrets estimated his net worth to range from approximately $2.8 million to more than $5.8 million. The numbers fluctuate, as such figures often do, shaped by markets and valuations. Still, they tell a clear story. Prosperity followed invention.

Long before he entered Congress as the representative for Kentucky’s 4th district, Massie had built something tangible in the private sector. After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he founded a technology company rooted in the emerging science of haptic feedback, machines that could simulate the sense of touch. He raised venture capital, hired engineers and secured patents.

The company grew. Investors believed.

When he eventually sold the firm, the years of design sketches, prototypes, negotiations, and risk condensed into financial return. It was not sudden fortune, but accumulated reward, capital forged from circuitry and persistence.

In a political world often shadowed by inherited wealth or lifelong incumbency, his assets trace back to entrepreneurship. Build a system. Prove its worth. Sell it. The arc mirrors his broader life pattern: identify a problem, construct a solution, and let the market, or the electorate, render its judgment.